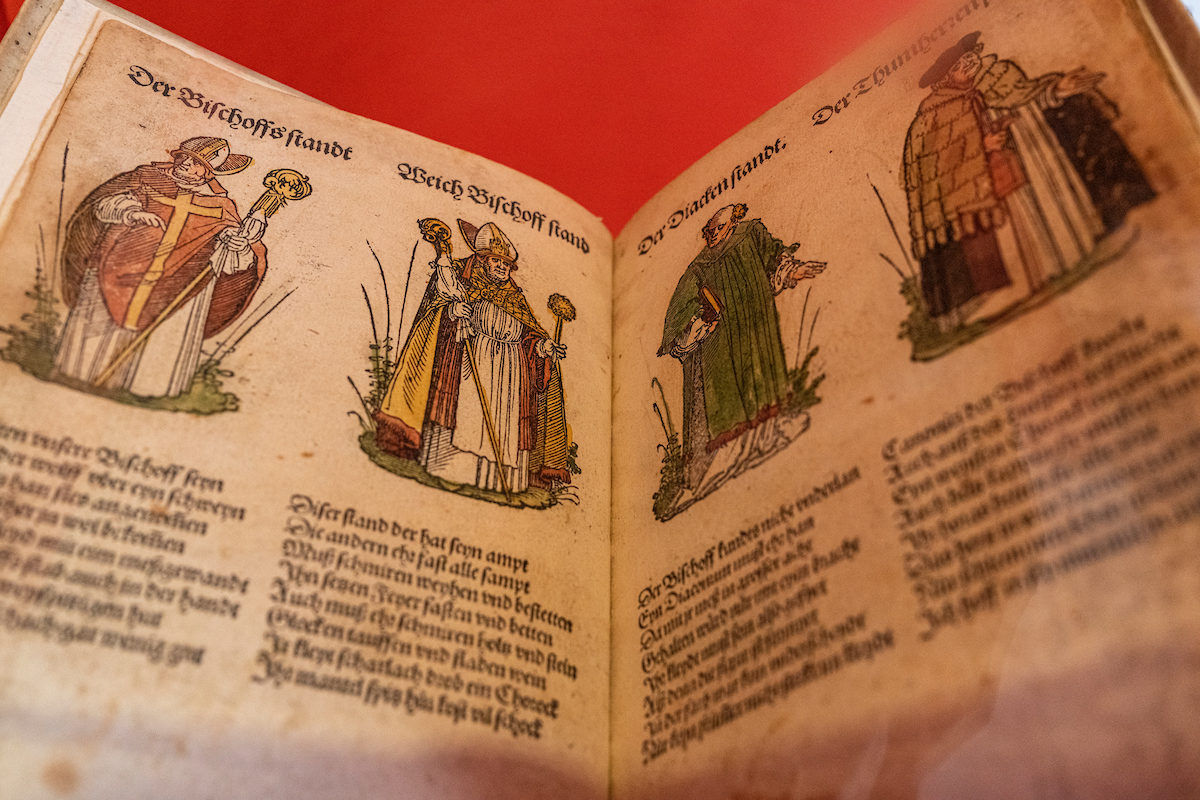

In the 16th century, 90% of people living in Europe were illiterate. While mass literacy was both encouraged and promoted under the Reformation, imagery continued to be used widely for communication purposes – provided the images themselves were not objects of devotion. The most radical reformers sought to minimize that risk in the first part of the 16th century through widespread efforts to destroy images and statues.

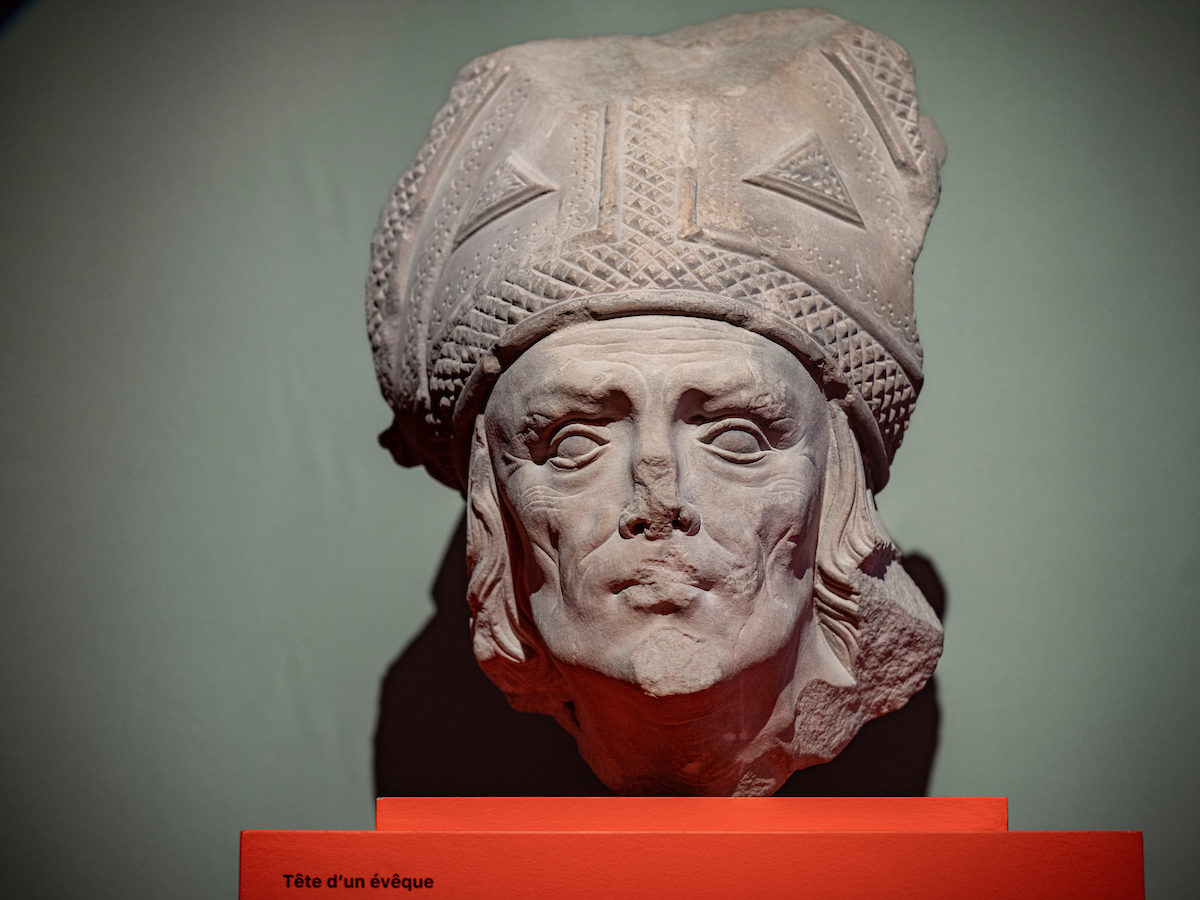

Their efforts are apparent in the objects presented in this room, including the remarkable bust of a Bernese bishop disfigured by the radicals. Facing that sculpture hangs the well-known portrait of Martin Luther by Lucas Cranach – one of the Museum’s most precious holdings – accompanied by other paintings of the famous reformer. Luther was aware of the power of images in promoting ideas, as demonstrated by Théodore de Bèze, whose famous Icons are shown here. That work, consisting of 36 engravings of reformers published in 1580, is an early visual presentation of a body of thought.

The battle of images was on. The intensity of that battle is apparent in this room, where anti-Protestant pieces are juxtaposed with anti-Catholic ones: the famous paintings of Calvin and Luther arriving in hell stand in contrast to the engraving of the pope in the guise of a devil.

Images were also used less provocatively in Christianity. Dutch artist Jan Luyken was one of many exceptional engravers whose works helped people understand the Bible. One of his engravings is on display here.